See all Lex Fridman transcripts on Youtube

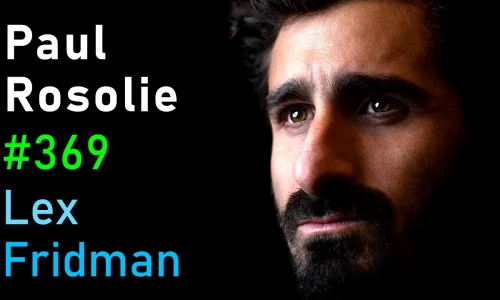

Paul Rosolie: Amazon Jungle, Uncontacted Tribes, Anacondas, and Ayahuasca | Lex Fridman Podcast #369

3 hours 34 minutes 57 seconds

🇬🇧 English

Speaker 1

00:00

It was just like 1 of those moments where we saw it at the same time and we're standing by the tail and the snake was so big that, I mean, this must've been a 25 foot anaconda dead asleep with a probably a 16 foot anaconda sprawled across her, and they're laying in the starlight and we're floating on top of a lake, standing there in the middle of the Amazon. And JJ just, I could feel the blood drain out of his face. And as a however old I was, maybe 20 years old, I just said, if we could somehow show people this, we'll be on the front cover of National Geographic and we can protect all the jungle that we want. And so I tried to catch it.

Speaker 1

00:47

Yeah, so I jumped on the snake and the only measurement I have of this animal is that when I wrapped my arms around it, I couldn't touch my fingers. And so I was, my feet were dragging, and to her credit, this anaconda did not turn around and eat me, because her head was this big. And she went and she reached the edge of the grass island and she starts plunging into the dark. And so I'm watching the stars vibrate as this anaconda is going.

Speaker 1

01:12

And I had to make the choice of either going headfirst down into the black, which no thank you, or stopping and just keeping my hand on this thing as it raced by me and I just felt the scales and the muscle and the power go by and then eventually taper down to the tail until it slipped away into the darkness and I was laying there just panting.

Speaker 2

01:36

The following is a conversation with Paul Rosley, a conservationist, explorer, author, filmmaker, and real-life Tarzan. Since for much of the past 17 years, Paul has lived deep in the Amazon rainforest, protecting endangered species and trees from poachers, loggers, and foreign nations funding them. He is the founder of Jungle Keepers, which today protects over 50, 000 acres of threatened habitat.

Speaker 2

02:03

And Paul is 1 of the most incredible human beings I've ever met. I hope to travel with him in the Amazon jungle 1 day, because in his eyes, I saw a truth that can only be discovered directly by spending time among the immensity and power of nature at its purest. This is the Lex Friedman Podcast. To support it, please check out our sponsors in the description.

Speaker 2

02:28

And now, dear friends, here's Paul Rosli. In 2006, at 18 years old, you fled New York and traveled to the Amazon. This started a journey that I think lasts to this day. Tell me about this first leap.

Speaker 2

02:44

What in your heart pulled you towards the Amazon jungle?

Speaker 1

02:47

From the time I was, you know, 3 years old, I'd say, you know, it was dinosaurs, wildlife documentaries, Steve Irwin, you name it. And like when my parents said, you know, nature versus nurture, they nurtured my nature. I was always just drawn to streams, forests.

Speaker 1

03:04

I wanted to go explore where the little creek led. I wanted to see the turtles and the snakes. And so I was a kid that hated school, did not get along with school. I was dyslexic and didn't know it, undiagnosed.

Speaker 1

03:15

I didn't read until I was like 10 years old, like way behind. And so for me, the forest was safety. Like I remember 1 time in first grade, they had you doing those, you know, those multiplication sheets. That was pure hell for me.

Speaker 1

03:28

And so I actually got so upset that I couldn't do it that I ran out, the classroom ran out the door and went to the nearest woods and I stayed there because that was safe. And so for me, like once I got to the point where I was like high school isn't working out, I had incredibly supportive parents that were like, look, just get out, take your GED, get out of high school after 10th grade. You gotta go to college, but like start doing something you love. And so I saved up and bought a ticket to the Amazon and met some indigenous guys.

Speaker 1

03:56

And the second I walked in that forest, it was like, It's like the first scene in Jurassic Park when they see the dinosaurs and they go, oh, this is it. I walked in there and just, I looked at those giant trees. I saw leafcutter ants in real life and I just went, oh. It was like the movie just started.

Speaker 1

04:12

That was when I came online.

Speaker 2

04:14

Can you put into words, what is it about that place that felt like home? What was it that drew you? What aspect of nature, the streams, the water, the forest, the jungle, the animals, what drew you?

Speaker 1

04:30

It's just, it's always been in my blood. I mean, for any forest, I mean, whether it's, you know, upstate New York or India or Borneo, but the Amazon, it's all of that turned up to this level where everything is superlatively diverse. You know, you have more plants and animals than anywhere else on earth.

Speaker 1

04:46

Not just now, but in the entire fossil record. It's the Andes Amazon interface, there's just, that's terrestrially, that's where it is. That's the greatest library of life that has ever existed. And so you're just, you're so stimulated.

Speaker 1

04:58

You're so overwhelmed with color and diversity and beauty and this overwhelming sense of natural majesty of these thousand year old trees and half the life is up in the canopy of those trees. We don't even have access to it. There's stuff without names walking around on those branches and it's like, it just takes you somewhere. And so going there, it was like, the guys I met just opened the door and they were like, how far do you wanna go down the rabbit hole?

Speaker 1

05:23

How much of this do you wanna see?

Speaker 2

05:25

You mentioned Steve Irwin. You list a bunch of heroes that you have, he's 1 of them. And you said that when you're unsure about a decision, you ask yourself, WWSD, what would Steve do?

Speaker 2

05:38

Why is that such a good heuristic for life? What would Steve do?

Speaker 1

05:42

He's a human being that like everything we saw from Steve Irwin was positive. Everything was with a smile on his face. If he was getting bitten by a reticulated python, he was smiling.

Speaker 1

05:52

If he was getting destroyed in the news for feeding a crocodile with his son too close, he was trying to explain to people why it's okay and why we have to love these animals. And everything was about love. Everything was about wildlife and protecting. And to me, a person like that, where you only see positive things, that's a role model.

Speaker 2

06:12

And it's just like an endless curiosity and hunger to explore this world of nature.

Speaker 1

06:17

Yeah, and an insatiable madness for wildlife. I mean, the guy was just so much fun.

Speaker 2

06:22

I got a, if it's okay, read to you a few of your own words. You open the book, Mother of God, with a passage that I think beautifully paints the scene. Before he died, Santiago Duran told me a secret.

Speaker 2

06:38

It was late at night in a palm-thatched hut on the bank of the Tampapata River deep in the southwestern corner of the Amazon basin. Besides a mud oven, 2 wild boar heads sizzling, sizzled in a cradle of embers, their protruding tusks curling in static agony as they cooked. The smell of burning cecropia wood and cinched flesh filled the air. Woven basket containing monkey skulls hung from the rafters where stars speak through the gaps in the thatching.

Speaker 2

07:12

A pair of chickens huddled in the corner conversing softly. We sat facing each other on sturdy benches across a table hewn from a single cross section of some massive tree now nearly consumed by termites. The song of a million insects and frogs filled the night. Santiago's cigarette trembled in the aged fingers as he leaned close over the candlelight to describe a place hidden in the jungle.

Speaker 2

07:40

That line, the songs of a million insects and frogs filled the night for some reason hit me. What's it like sitting there conversing among so many living creatures all around you?

Speaker 1

07:52

Every night in the jungle, you live in constant awareness of that out there in the darkness are literally millions of heartbeats around you. And so like, we exist in this, you know, domesticated, paved world most of the time, but when you go out there past the roads and the telephone poles and the hospitals and you make it out into earth, just wild earth. And there's no, it's not like this is a national park.

Speaker 1

08:21

There's no rescue helicopter waiting to come get you. You are out there and you're surrounded at night by, I mean, there are snakes and jaguars and frogs and insects and all this stuff just crawling through the swamps and through the trees and through the branches. And we put on headlamps and go out into the night and just absolutely fall to our knees with wonder of the things that we see. It's absolutely incredible.

Speaker 2

08:43

And most of it doesn't make sounds like the insects do.

Speaker 1

08:46

The insects do, the frogs do, you have some of the night birds making sounds, but a lot of it, everything has evolved to be silent, invisible. I mean, everything there is on the list. There's another line in Mother of God where I said, you know, like life is just like a temporary moment of stasis and like the churning, recycling death march that is the Amazon.

Speaker 1

09:06

Like it's been called the greatest natural battlefield on earth. I mean, in any square acre, there's more stuff eating other things than anywhere else. And you go through a swamp in the Amazon and there's like, there's tarantulas floating on the water, there's frogs in the trees, there's tadpoles hanging from leaves waiting to drop into the water, There's fish waiting to eat them, there's birds in the trees. You literally are surrounded by so many things that your brain can't process it.

Speaker 1

09:36

It's just overwhelming life.

Speaker 2

09:41

Churning Death March. Some of the creatures are waiting and some of them are being a bit more proactive about it. What do you make of that churning death march?

Speaker 2

09:54

That the amount of murder that's happening all around you at all scales. What is that, you know, We dramatize wars and the millions of people that were lost in World War II, some of them tortured, some of them dying with a gun in hand, some of them civilians, but it's just millions of people. What about the billions and billions and billions of organisms that are just being murdered all around you? Does that change your view of nature, of life here?

Speaker 1

10:27

I've always kind of wondered like that, like when you see like a wildebeest taken down by lions and eaten from behind while it's alive. And it makes you question God. You know, you go, how could they let this happen?

Speaker 1

10:41

In the Amazon, I find personally that these natural processes make up almost a religion, that it reminds you how temporary we are, that the bot flies that are trying to get into your skin and the mosquitoes that are trying to suck your blood and that when you sweat, you see the, you literally can like hold out your arm and watch the condensation come off of your skin and rise up into the canopy and join the clouds and rain back down in the afternoon. And then you drink the river and start it all over again. And it's like, it's flowing through you. So the Amazon reminds me that there's a lot that we don't understand.

Speaker 1

11:24

And so when it comes to that overwhelming and collective murder, as Werner Herzog put it, It's just part of the show. It's part of the freak show of the Amazonian night. I see you, at

Speaker 2

11:38

certain moments, able to feel 1 with a mosquito that's trying to kill you slowly.

Speaker 1

11:44

1 with the mosquito is a stretch.

Speaker 2

11:47

Is it always the enemy? What I mean is like you're part of the machine there, right?

Speaker 1

11:50

Yeah, and it's like fair play. It's like fair play. So like we have bullet ants and like, you know, you get nailed by a bullet ant and you

Speaker 2

11:56

just go, yeah, well done.

Speaker 1

11:58

Well done. Today's over, I'm going back to bed and I'm taking a pile of Tylenol.

Speaker 2

12:02

Do you think in that sense, when you're out there, are you a part of nature or are you separate from nature? Is man a part of nature or separate?

Speaker 1

12:11

I think that's what's so refreshing about it, is that out there you truly are. And so whether we're bringing researchers or film crews or whether we're just out there ourselves on an expedition, you truly are a part of nature. And so 1 of the things that my team and I started doing when I became friends with these guys, this is a family of indigenous people from the community of Inferno, and they took me in.

Speaker 1

12:36

And as we got close, they started saying, you can come with us on our annual hunting trip. And I went, okay. And it's 4 guys in a boat, and you don't wanna get your clothes wet, so we're all in our boxers in a canoe with a motor going out past the places that have names, and you're out in the middle of the jungle. And the thing is, when your motor breaks, you are so quickly reminded of the inerrant truths, like the things that nobody can argue with.

Speaker 1

13:08

And we live in such a human world where everything is debatable, religion and politics and perspectives on everything. And then you get down to this point where it's like, if we don't figure something out, the river is going to rise and take the boat. That's the truth, and ain't nobody gonna argue with that. And it's like, to me, there's a beauty in that truth, because then all of us are united there in that truth against the natural facts around us.

Speaker 1

13:34

And so to me, that's a state where I feel very, very at home.

Speaker 2

13:38

And the Amazon is more efficient than most places on earth at swallowing you up. God, yeah. Okay.

Speaker 2

13:46

Yeah. So just to linger on that, because you've spoken about Francisco de Arellana, who's this explorer in

Speaker 1

13:56

1541

Speaker 2

13:56

and 42 that sailed the length of the Amazon. Yeah. Probably 1 of the first.

Speaker 2

14:00

And there's just a few things I should probably read. I should probably find a good book on him because the guy seems like a gangster.

Speaker 1

14:07

Yes, there's some great books on him.

Speaker 2

14:09

So he sailed, he led the expedition that sailed all the way from 1 end to the other. There's like a rebuilding of a ship.

Speaker 1

14:18

Which is insanity.

Speaker 2

14:19

Yeah. Yeah. So because it speaks to the thing, it's like nobody's gonna come and rescue you. No.

Speaker 2

14:24

You have to, if your boat dies, you're gonna have to rebuild it.

Speaker 1

14:29

Yeah, so they came down the Andes, entered in the headwaters of the Amazon, constructed some sort of raft, boat, craft, something, and made it down the entire Amazon basin. Of course, his stories are the ones that led to the Amazon being called the Amazon, because he reported tribes of women. He reported these large cities, places where the tribes lived on farms of river turtles that they corralled and they lived off of that protein.

Speaker 1

14:52

And then when they came out to the mouth of the Amazon, if I remember it correctly, that just through navigation and the stars, they were able to calculate where the way was back to Spain and make a boat seaworthy enough to bring them home.

Speaker 2

15:06

Incredible, absolutely incredible. Do people like that inspire you, your own journey? Like what gives you kind of strength in these harshest of times and harshest of conditions, you can persevere.

Speaker 1

15:19

Yeah, I mean, you look at the stories of people that are so, you know, these stories of people that have overcome incredible suffering like that, or like, you know, what Shackleton did or something like that. And so like when you're, you know, I've been, you know, your tent gets washed away, you go to sleep and the river rises 20 feet and washes away your tent and you crawl out and all you have is a machete and a headlamp, literally no bag, no food, no nothing, and you go, wow, the next 6 days before I reach back to a town is gonna be just pure hell. I'm gonna be sleeping on the ground, covered in ants, destroyed by mosquitoes.

Speaker 1

15:50

And then it becomes, am I in any capacity, any percentage as tough and resilient as the people that I've read about, that have made it through things far worse than this? And then that's the game you play.

Speaker 2

16:03

What goes through your head? All you got is the headlamp and the machete. So are you thinking at all?

Speaker 2

16:10

Like I've gotten a chance to interact quite a lot with Elon Musk, and he constantly puts out fires having to run several companies. There's never a kind of whiny deliberation about issues. You just always, 1 step forward, how to solve, right? This is the situation, how do you solve it?

Speaker 2

16:29

Or do you also have a kind of self-motivating, almost egotistical, like I'm a bad motherfucker. I can handle anything. Almost like trying to fake it till you make it kind of thing.

Speaker 1

16:41

There was a little bit of that. With your machete and everything. I got a sword.

Speaker 1

16:47

There may have been a little bit of that when I was like 14, 15 years old, I'd have a hunting knife and my dog and I'd go out into the woods with the cat skills and survive for a weekend. My rule was 1 match. You get 1 match and you got to make shelter. And then I'd bring like a steak and make a fire and stuff.

Speaker 1

17:05

And at that point there may be with some ego, but in the Amazon, you get stripped down so completely that you, it's like that thing, like, watch the atheism leave everyone's body when they think they're about to die. It's like when you find yourself staring up at the Amazon at night and you go, there is no hope of getting out of here. I mean, I was once lost in a swamp where it took me days to get out of there. And there was moments where I just said, this is clearly it, there's no ego there.

Speaker 1

17:34

There's just hope. You start realizing what you believe in and praying that you'll be okay and then trying to summon whatever you know about how to survive and that's it. And so it's actually, again, it's kind of a blissful state if you can walk that line between adventure and tragedy and sort of keep yourself right at that very, very fine line without going over.

Speaker 2

17:58

Ever fear of death? Fear, Ever fear? Terror?

Speaker 1

18:02

No, I don't want to die. I wanna, you know, I love the people in my life and there's a lot of things I wanna do, but every time I've been certain that I'm gonna die, it's been, I've been very, very calm. Very calm and just sort of like, okay, well, if this is how the movie goes, then this is how it goes.

Speaker 2

18:20

Almost accepting.

Speaker 1

18:21

Yeah, which is reassuring.

Speaker 2

18:24

You mentioned Herzog. Just to venture down this road of death and fear and so on, There's been a few madmen like you in this world. He's documented a couple of them.

Speaker 2

18:39

What lessons do you draw from Grizzly Man or Into the Wild, those kinds of stories? Were you ever afraid that you would be 1 of those stories?

Speaker 1

18:48

Oh yeah, I actually think that it's in Mother of God where I said I almost into the wilded myself. Like I went out there and really I got so lost and so destroyed that I said this is gonna be the next 1. This is gonna be the next story of some idiot kid from New York who went to the Amazon thinking he was Percy Fawcett and then vanished.

Speaker 1

19:06

Because if you do vanish out there, your body's gonna be consumed in a matter of days. Like 2. You know, if we see an animal dead on a trail, you got dung beetles and fly larva and vultures and there's a whole pecking order. You get the black vultures, the yellow vultures, the king vulture, they all come in.

Speaker 1

19:23

That thing is picked clean in a couple of days.

Speaker 2

19:25

What would be the creature that eats most of you in that situation?

Speaker 1

19:29

Probably the vultures. Probably the vultures and the maggots. It's really quick, it's really, really quick.

Speaker 1

19:37

Like even as far as like you can't leave food out. You know, like if you have like a piece of chicken, you say, oh, I'll eat it in the morning. You leave it

Speaker 2

19:43

out, you can't do that. It's not good by morning. Grisly Man, for example, like what, because that's a beautiful story.

Speaker 2

19:50

It's both comical and genius, and especially the way Herzog tells it. Well, first, do you like the way he told the story? Do you like Herzog?

Speaker 1

19:58

I do, I love Herzog, and I love his documentary, The Burden of Dreams, which is in the Amazon, not very far from where I work. And the sheer madness that you see this man undergoing of just trying to recreate hauling a boat over a mountain is wild. And the extras that he hired to play the natives are the, I think they're Machiganga tribesmen and they just look like all the guys that I hang out with and it's like, they're doing all this stuff in the jungle that months and months and months and you can just see him deteriorating with madness because the jungle, you know, your boat, you know how many times I've tied up a boat to the side of the river?

Speaker 1

20:39

This just happened like a year and a half ago. I tied up, through COVID, I pretty much just lived in the jungle for a while. And there was nobody there and there was no support and I tied up my boat and the rain is just hammering. Like the universe is trying to rip the earth in half.

Speaker 1

20:53

The rain is just going and the river's rising and I tied up the boat, but then you go to sleep and you gotta wake up every 2 hours to go check the boat. And the boat is thrashing back and forth. So all night, every 2 hours I'd wake up barefoot in driving rain, like golf ball raindrops and just go down and check the boat. And then by morning I was like, I fell asleep, woke up, checked the boat and then I was like, I'm just gonna go make coffee, I was so done.

Speaker 1

21:16

I was so like at the end of my rope every time bailing the boat out and stuff. And then we got 15 minutes of heavy rain that filled the boat, sank it. And so now I'm stuck up river with no boat. And it's like that type of thing where it's like no matter how hard you try, the jungle's just like, listen, you're nothing.

Speaker 1

21:33

You are nothing. And so it's that constant reminder. And so Herzog really threw himself into that, in that film. And it's brilliant to watch.

Speaker 2

21:42

What do you think he meant by the line that you include in your book? It's a land that God, if he exists, has created in anger. Said in a German accent.

Speaker 1

21:54

Yeah, overwhelming and collective murder.

Speaker 2

22:00

So that's, so you didn't really appreciate the beauty of the murder.

Speaker 1

22:05

I think he appreciated it, but to him it was very dark. You know, I think he saw the darkness in it. And that's there, it sure is.

Speaker 1

22:13

As soon as you do Ayahuasca, that door opens and you see the darkness, because that brings you right into the jungle, like the heart of it. But I think that for him, I think that darkness is something that he embraces and that he loves. There's another film of his, and I don't know if this is accurate, but my memory has it that there's a penguin, and I think it's in Antarctica, and the penguin's going in the wrong direction, away from the ocean. And I feel like he goes on this monologue about how he's just had enough.

Speaker 1

22:43

This 1 penguin is just marching towards, you know.

Speaker 2

22:46

Well, his, because I remember that clip from that documentary, and what Werner says is that the penguin is deranged. Yes. That he's lost his mind.

Speaker 2

22:57

And I took offense to that. Yeah. Because maybe that's a brave explorer. Like how do you know there's not a lot more going on?

Speaker 2

23:06

Like it could be a love story. Those penguins get super attached.

Speaker 1

23:11

Maybe his mate was over there and

Speaker 2

23:12

he had

Speaker 1

23:13

to go find her.

Speaker 2

23:14

Or it's a lost mate and he last time he saw her was going in that direction. So this is like the great explorer. We assume animals are like the average of the bell curve.

Speaker 2

23:24

Like every animal we interact with is just the average, but there's special ones, just like there's special humans. That could be a special penguin.

Speaker 1

23:31

It could have been. And I had the same thought where I was like, I found it beautiful how he interpreted it. What I took away from that was I found that Werner Herzog's monologue there was brilliantly dark and also comedic, but maybe irrelevant biologically speaking towards penguins, which happens a lot with animals.

Speaker 1

23:53

I find there's so many times where I'll find people be like, do you think that animals can show compassion? And you hear a bunch of people that have never left the pavement talking about, wow, this 1 animal helped another animal. It's like, go ask Jane Goodall if animals can show compassion. Go talk to anybody that works on a daily basis with animals.

Speaker 1

24:13

And so like to me, there's always a little bit of frustration in hearing people sort of like pleasantly surprised that animals aren't just, you know, these automatons of, you know, just, what's the word, like programmed, you know, nothingness.

Speaker 2

24:30

First of all, what have you learned about life from Jane Goodall? Because she spoke highly of your book and you list her as 1 of the mentors, but what kind of wisdom about animals do you

Speaker 1

24:40

draw from her? The wisdom from Jane is so diverse. I mean, first of all, she's someone that, the work that she did at the time she did it was so incredible because, I mean, she was out there at a very young age doing that field work.

Speaker 1

24:55

She was naming her subjects, which everyone said you shouldn't do. She broke every rule. She broke every rule. She was assigning, and everyone said, you're anthropomorphizing these animals by saying that they're doing this and that.

Speaker 1

25:06

And she was like, no, they're interacting. They're showing love, they're showing compassion, they're showing hate, they're showing fear. And she broke straight through all of those things. And it paid off in dividends for her.

Speaker 2

25:19

Do you see the animals as having all those human-like emotions of anger, of compassion, of longing, of loneliness, from what you've seen, especially with mammals, or with different species out there?

Speaker 1

25:33

Do they have all that? It depends on the animal. You know, if you're talking, you know, on the scale of a cockroach to an elephant, you know, it's like a lot of these things, and I wonder about this stuff all the time, you know.

Speaker 1

25:43

I'll have a praying mantis on my hand and just go, what is going through your mind, you know? Or you'll see a spider make a complex decision and go, I'm gonna make my web there. You know, and you go, how are you doing this? How are you, because he made a calculation there, you know, it's smart.

Speaker 1

25:58

I was in the jungle not that long ago, and I was walking, and all of a sudden, this dove comes flying through the jungle, right up to my face. Lands on a branch, like right here, right next to me. I look at the dove, dove looks at me and she's like, hey, and she's clearly like panting. And I'm like, why are you so close to me?

Speaker 1

26:14

This is weird. And she's like, I know. And then an ornate hawk eagle flies up 10 feet away, looks at both of us and just like scowls and like sticks up its head feathers and then just like flies off. And the dove was like, sweet, thanks.

Speaker 1

26:26

And then flew in the other direction. And I was like, dude, you just used me to save your life. Yeah. The dove knew.

Speaker 2

26:32

See, this is what, because there's Mike Tyson and there's Albert Einstein. And sometimes I wonder when I look at different creatures, even insects, like is this Mike Tyson or is this Einstein? Because 1, or other kinds of personalities, is this a New Yorker or is this a Midwesterner?

Speaker 2

26:52

Or is this like a San Francisco barista of the insects? Like there's all kinds of personalities, you never know. So you can't like project, like if you run into a bear and it's very angry, it could be just the asshole New Yorker for you. Yeah, sure, sure.

Speaker 2

27:08

As opposed to.

Speaker 1

27:09

What are you saying about

Speaker 2

27:09

New Yorkers, man? Exactly, point well made. So Speaking about communicating with a dove, you first met the crew in the Amazon.

Speaker 2

27:20

You talk about JJ as somebody who can communicate with animals. What do you think JJ is able to see and hear and feel that others don't, that he's able to communicate with the animals.

Speaker 1

27:32

When I say this is the most skilled jungle man I've ever seen, and I know so many guys in the region, he has libraries of information in his cranium that we cannot fathom. It's just stunning. I have seen him use medicinal plants to cure things that Western doctors couldn't cure.

Speaker 1

27:55

I've seen him navigate in such a way that he's not using the stars. He's not using any discernible, it's like when elephants, sometimes you'll watch a herd of elephants and they'll be like, yo, let's go, we're going this way, and you'll see them sort of communicate, but there's no audible sound. They'll just decide that they're going that when they all do it. JJ has this way in the jungle of, he'll stop and he'll go, wait, and you go, what is it?

Speaker 1

28:18

And he goes, there's a herd of peccary coming. And I'm like, where? Based on what? And he's like, just wait, you'll see.

Speaker 1

28:27

And he'll sit there.

Speaker 2

28:30

You think that's just experience?

Speaker 1

28:31

It's incredible experience. It's growing up barefoot in the Amazon. And the gift is that he can speak fluent English.

Speaker 1

28:38

And so when I bring tourists and scientists or news reporters down there, he can communicate with them. He's actually good on camera because he doesn't care about cameras. And like, you know, for instance, we were walking up a stream a few months ago, and I went, hey, look, jaguar tracks. And he went, oh, and I was like, what, jaguar tracks?

Speaker 1

28:59

And he's like, no, look, look harder. And I was like, the toes are deeper than the back. And he was like, uh-huh, and where are they? And I was like, by the water.

Speaker 1

29:08

And I was like, the jaguar's drinking. It was leaning to drink. And he was like, that's right. He's like, now look behind you.

Speaker 1

29:13

I look behind me, and there's scat. There's a big log of jaguar shit sitting there, it's got butterflies all over it. Fresh, pretty fresh. And then there's another 1 that's less fresh.

Speaker 1

29:23

And so he's teaching me as he does, he's going look at this, look at this, is that 1 as fresh as this 1? No, and then he goes now look up, look up. There's 3 vultures above us. The kill is near us.

Speaker 1

29:35

The jaguar has been coming multiple times to the river to drink as it's feasting on whatever it killed. And he's going, it's within 30 feet of us right now. And it's like, I'm like, Oh look, impressions in the sand. He's like, I just drew 19 conclusions from that.

Speaker 1

29:48

It's like watching Sherlock Holmes at work.

Speaker 2

29:50

It's just- Constructing the crime scene. Incredible. Does that apply also to be able to communicate with the actual animals, like read into their body movements directly, into their, whatever that dove was saying to you, you'd be able to understand.

Speaker 2

30:08

Or is that all just kind of taken in the complex structure of the crime scene, of the interactions of the different animals, of the environment and so on? Like, what is that, that you're able to communicate with another creature, that he was able to communicate with another creature?

Speaker 1

30:21

He knows the intention of pose, he knows the habits, he knows the perspective. When he talks about animals, he'll talk about each species as if it's a person. So he'll say, oh, 0, the jaguar, she never likes to let you see her.

Speaker 1

30:37

And so he'll come back from the jungle and he'll go, oh, I was watching monkeys and this jaguar was also watching the monkeys, but I was being so quiet, she didn't see me. And then when she see me, she feels so embarrassed and she'd go. And he'll tell you this story like as if he had this interaction with like his neighbor. And you know, and he'll be like, oh, the Puka Kunga, it never does that.

Speaker 1

30:56

You won't see it do that. And so 1 time he caught a fish and I was such a big fish. It was this big, beautiful pseudoplatystoma, this tiger catfish, this amazing old fish, and they're all excited to eat it, and I felt so bad watching this thing gasp on the sand, and I went, you know what? We don't need this.

Speaker 1

31:12

This is for fun. Threw it back. Oh, no. And then I took my hand, and I went, and I made like drag marks, so I could say, oh, it snuck back in the water.

Speaker 1

31:22

And so he walks up, he looks at it, and he was like, I hate you. And I went, what, no, I said, it must have just, he went, That's not what happens. He goes, it goes like this when it goes, he knew the track of a fish. And I was like, all right, JJ, I'm sorry.

Speaker 1

31:37

I'll catch you another fish.

Speaker 2

31:40

So stepping back to that way you open mother of God.

Speaker 1

31:43

Yeah.

Speaker 2

31:45

Who was Santiago Duran and what secret did he tell you?

Speaker 1

31:47

JJ's father was, at some point he was a policeman. At some point when he was a teenager, he was working on the boats that before this little gold mining city of Puerto Maldonado grew, the only way to get supplies in was to take canoes up the Tambopata River up to the next state, which is Puno, and where mules would come down from the mountains with supplies and then he'd pilot the boats down, but they didn't have motors at that time, So he would be pulling the boat. So he was, he became this physically terrifying man.

Speaker 1

32:20

And I met him in it when he was in his eighties and he was still living out in the jungle by himself. And I mean, he's seen an anaconda eat a taper, which is the, you know, a cow sized mammal in the Amazon. He'd seen uncontacted tribes face to face. He once killed an 11 foot electric eel, opened the back of the thing's neck, removed the nerve that he says was the source of the electric, then he cut his forearm, placed that nerve into his forearm, wrapped it with a dead toad, and claimed that it would give him strength through the rest of his life, and continued to be a jungle badass until the day he quietly leaned back at a barbecue and ceased to be alive.

Speaker 1

33:02

The man was incredible. But the secret that he told us was that if you wanna find big anacondas, if you wanna see the Yakumama, he was like, you have to go to the Bawayo, the place of Boas, the place that we came to call the floating forest. And so he sent us there and it became like this pilgrimage. In the Amazon, a lot of the creation myths are based around the anaconda coming down from the heavens and carving the rivers across the jungle.

Speaker 1

33:30

And if you look at the rivers, it looks like that. It looks like the path of an anaconda crawling through the jungle. It's even the right color. And so from the reference to the tribes of women, the Amazons, to the anaconda mother, everything in the Amazon is very feminine based.

Speaker 1

33:47

Even the trees, the largest trees in the jungle, the mother of the forest, the Madre de la Selva, is the Capoc tree. And it's just this monster tree, these beautiful ancient trees. And that was the beginning of the transition that we made from me being like, I hate school, I wanna go on adventures. Jane Goodall got to do all this amazing stuff, I'm just a kid stuck here, to eventually becoming something that had to do with where my identity became the jungle, where my life became the jungle.

Speaker 1

34:19

The secret that he told us opened that door because when we started working with these giant snakes, it started getting attention. It started getting people to go, what are you doing? And it started allowing me to have experiences that solidified and nailed down the fact that this wasn't just like a weekend retreat. This was something that I was born to do.

Speaker 2

34:44

And gave you more and more motivation to go into these uncharted territory of the Yakumama. Which, just to step back, what nations are we talking about here? Is there some geography?

Speaker 2

34:59

What are we talking about? Where is this? So I'm in Peru. Yeah.

Speaker 2

35:02

We're in Peru. Which is a South American nation.

Speaker 1

35:05

Peru is a South American nation. Brazil has 60% of the Amazon, which is unfortunate because anything that happens politically in Brazil has a massive impact on the Amazon. Peru has the Western Amazon and Ecuador has a little bit of the Western Amazon.

Speaker 1

35:21

And the Western Amazon is where the Andes Mountains, the cloud forests, which is a mega biodiverse biome, falls into the Western Amazon lowlands. And so you have the meeting of these 2 incredible biomes, and that's what makes this like superlative, incredible, glowing moment of life on earth. So yeah, we're in Peru in the Madre de Dios, which is the mother of God, which I always thought was such a beautiful, you know, the jungle is the source of all life. And so we were with the Eze-Eja people and they belong to a community that's called Inferno, which was given by the missionaries who when they tried to go bring these people, Jesus got so many arrows shot at them that they just called it hell.

Speaker 1

36:05

And so Santiago Duran helped unite these tribes that were sort of scattered through the jungle and get them status, government recognized status as indigenous people. So he was sort of a hero. He was sort of a legend for a lot of the stuff he'd done out barefoot with just like a rifle and a machete in the jungle. He had 19 children?

Speaker 1

36:27

And the last 1, I think the 20th child that he adopted was a refugee from the Shining Path that floated down the river and he just took him in. And this is just a guy that was a, everything he did, like when he died, the whole region showed up. It was, he was somebody. So just the fact that I know him gives me street credit.

Speaker 1

36:46

Like the fact that I knew him, I can go like, oh, I knew Santiago and people are like, no. I'm like, yeah, yeah.

Speaker 2

36:51

So you had to get integrated to the culture, to the place in every single way, which is tough for you for being from New York.

Speaker 1

37:00

Yeah, yeah, it could have been tough, but I took to it. The jungle, they were very, JJ's teaching me about medicines, and we were doing bird surveys, and taking data on macaw populations, and JJ was just like, you really wanna, He goes, you gotta sleep. And I was like, I only have a few weeks here.

Speaker 1

37:18

I don't know if I'm ever gonna come back. I'm never going to sleep. So we'd be out every night looking for all the wildlife we could. I wanted to take photos.

Speaker 1

37:24

I wanted to see things. And then the exchange came with that. He was like, I'm terrified of snakes. And I said, well, I've always worked with snakes.

Speaker 1

37:32

I said, I'll teach you how to handle snakes. And then we just had this like little exchange. And when I left after my first time back in 2006, you know, I said, how can I help? And they were like, look, you know, we're out here trying to protect this little island of forest that is going to be bulldozed.

Speaker 1

37:53

And the more people that you can bring, the more knowledge and the more awareness that you can bring to this, it'll help. And so really at that age, at 18 years old, I sort of started dabbling with the idea of that I could be part of helping these people to protect this place that I loved. And of course at that time, that idea seemed like too large of a dream or too large of a challenge to that I could actually impact it.

Speaker 2

38:20

So what was the journey of looking for these giant snakes? Of looking for anacondas?

Speaker 1

38:28

And what are anacondas? Anaconda is the largest snake on earth. So you have reticulated pythons in Southeast Asia.

Speaker 1

38:36

They're actually longer, but anacondas are these massive boas. They give live birth and unlike a lot of other species, So an anaconda starts off, you know, a little 2 foot anaconda, just a little thicker than your finger, a little baby. And they're food for cane toads, herons, crocodiles, you name it, they're pretty harmless, defenseless. But as they grow, they're eating the fish, they're eating the crocs, and then they grow a little more and they're eating things like capybara and they're eating larger prey.

Speaker 1

39:05

And then at the end of their life, a female anaconda, you're talking about a 25, 30 foot, 300, 400 pound snake with a head bigger than a football. And these things, that means that they impact the entire ecosystem, which

Speaker 2

39:20

is very unique. Moves up the food chain to become basically an apex predator.

Speaker 1

39:25

Yeah, apex predator. Yeah, the apex predator of the rivers. And so.

Speaker 2

39:29

That's how interesting, it's just eating your way up the food chain.

Speaker 1

39:31

Eating your way up the food chain, if you can survive. And like, they're constantly at war with everything else. But, you know, so I showed up in the Amazon.

Speaker 1

39:39

I was like, so where are the anacondas at? And they were like, oh, no, no, no, it's not like that. They're like, it's, you have to find these things. They're subterranean.

Speaker 1

39:46

They're living in the special swamps. People kill them. And so we went to the floating forest after we'd come back from an expedition. We'd call it like a 12 foot anaconda.

Speaker 1

39:58

Now it's become like this like classic photo of me and JJ with this anaconda over our shoulders. And we were like, we 12 days out in the jungle on a hunting trip. And we came back and we showed his dad and Santiago looked at us and he was like, that's the smallest anacondita I've ever seen. He's like, you guys are pathetic.

Speaker 2

40:15

Oh man, 12 foot.

Speaker 1

40:17

And he was like, look, you go to the, go. He was like, go. He's like, I'm giving you permission, go to the Bihuahua, go to the floating forest.

Speaker 1

40:22

And so we went to this place and we reached there at night and it was me, JJ, and 1 of his brothers. And his brother took 1 look at it and was like, I'm out. And he started walking back. And me and JJ get to the edge of this thing.

Speaker 1

40:35

And this is our friendship. It's both us 2 idiots pushing each other farther and farther. And I put a foot on the ground and it all shook. And the stars are reflecting on the ground.

Speaker 1

40:47

And what we realize is that it's a lake with floating grass on top of it. And there's islands of grass floating on this lake, very life of Pi, and the tops of trees are coming out of the surface of the water. And so we start walking across this and JJ's going, these are big anacondas. And I'm going, JJ, that's a 2 foot wide smooth path snaking through the grass, there's no anaconda that big.

Speaker 1

41:13

He was going, shh, they're listening. I said, they don't have ears. He goes, they're listening. And he's like, we're walking and we're walking.

Speaker 1

41:20

And then it's like, maybe it's like 1 a.m. Or something. And it was just like 1 of those moments where we saw it at the same time and we're standing by the tail. And the snake was so big that, I mean, this must've been a 25 foot anaconda dead asleep with a probably a 16 foot anaconda like sprawled across her.

Speaker 2

41:44

And

Speaker 1

41:44

they're laying in the starlight and we're floating on top of a lake standing there in the middle of the Amazon. And JJ just, I just, I could feel the blood drain out of his face. And as like a, however old I was, you know, maybe 20 years old, I just said, if we could somehow show people this, We'll be on the front cover of National Geographic and we can protect all the jungle that we want.

Speaker 1

42:08

And so I tried to catch it. So I jumped on the snake and the only measurement I have of this animal is that when I wrapped my arms around it, I couldn't touch my fingers. Yeah. And so I was, you know, my feet were dragging and to her credit, this anaconda did not turn around and eat me because her head was, you know, this big.

Speaker 1

42:27

Yeah. And she went and she reached the edge of the grass island and she starts plunging into the dark. And so I'm watching the stars vibrate as this anaconda is going. And I had to make the choice of either going head first down into the black, which no thank you, or stopping and just keeping my hand on this thing as it raced by me and I just felt the scales and the muscle and the power go by and then eventually taper down to the tail until it slipped away into the darkness and I was laying there just panting.

Speaker 1

42:59

And then I turned around and went, JJ, what the fuck? Like, where were you, man?

Speaker 2

43:02

And

Speaker 1

43:02

he was just like completely white, circuits blown, and I had to go then take care of him. I was like, are you okay? He was like, no.

Speaker 1

43:11

He just couldn't. So we came back with that, and then after that, we were like, okay. Clearly, the parameters of reality that we thought were possible are just a tiny fraction of what's out there. Like we now, that sort of recalibrated us.

Speaker 1

43:25

We were like, okay, we're rubbing up against things that are bigger than we thought were ever possible. And So we were like, okay, now we need to concentrate on this.

Speaker 2

43:34

So how dangerous is that creature to humans?

Speaker 1

43:39

To humans, not at all. I mean, our cook's father-in-law was eaten by an anaconda, but like, you know, then again like how- Look

Speaker 2

43:48

at the way you say that story. Sometimes it happens.

Speaker 1

43:51

It happens. I mean, come on, every now and then somebody gets stung by a bee and dies. Like, you know, it's once in a while it happens, but you gotta have a really big anaconda, really hungry.

Speaker 1

44:00

And like anybody that works in the wild, I mean, just, you know, if you walk up to a crocodile, even a giant Nile crocodile, you walk up to them, most of the time they're gonna run into the water. They don't want confrontation. They hunt in their way, on their terms, sneaky. You're not gonna see them.

Speaker 1

44:16

And so with an anaconda, it's like, yeah, if you're, I mean, the guy who got eaten, like if you're drunk and you go to the edge of the water and you go for a midnight swim by yourself in an Amazonian lake, I mean, whose fault is that?

Speaker 2

44:27

But if you jump on an anaconda and try to,

Speaker 1

44:30

yeah,

Speaker 2

44:30

try to hold on, then you're safe.

Speaker 1

44:33

Apparently. I mean, I think at this point, we've, you know, the research we've done, I think I've handled or caught, you know, over 80 anacondas in the field, and not 1 of them has bitten me. They always choose flight over fight. They're like, just leave me alone, let me go.

Speaker 1

44:48

I'm just gonna crawl under this thing. They're not an aggressive animal. I mean, no snake, no, I actually like, I kind of like, the only time I get particular with like, you know, the words is like, people go, that's an aggressive, black mambas are aggressive. I go, no snake is aggressive.

Speaker 1

45:04

A rattlesnake is gonna rattle to say, hey, back up. A cobra is gonna stand up and show you its hood and people go, oh, look, he's being aggressive. No, he's not being aggressive. He's going, don't step on me.

Speaker 1

45:13

Don't make me do this. They're actually being very peaceful. That's the way I look at it. Because if there was a cobra in the corner of this room right now, he would crawl under the curtain and we'd never see him again.

Speaker 2

45:23

Yeah, it's like Genghis Khan, before conquering the villages, he always offered for them to join the army.

Speaker 1

45:28

Doesn't need to be like this.

Speaker 2

45:30

Yeah, join us, nobody gets destroyed. If you want to be proud and fight for your country,

Speaker 1

45:38

then we're

Speaker 2

45:38

gonna have to

Speaker 1

45:39

deal with it. Oblige him.

Speaker 2

45:41

Exactly, okay. So how do you catch, Actually, let's step back because there is, in part, you are a bit of a snake whisperer, so what is it that others don't understand that you do about snakes? What's maybe a misconception?

Speaker 2

46:00

Or what have you learned from the language you speak that snakes understand?

Speaker 1

46:06

I don't know, it's an animal that has many times in my life I've been responsible for helping. I started catching snakes when I was very young. I'd watch Steve Irwin and go out and catch a garter snake or a black rat snake in New York.

Speaker 1

46:22

And then I had a rule. I said I have to catch 100 non-venomous snakes before I'm allowed to handle a venomous snake, if I ever need to handle a venomous snake. And then I was on a trail 1 time, I think in Harriman State Park, and some guy, like some big hero, he tells us, you know, he's like, back up,

Speaker 2

46:36

I'm

Speaker 1

46:36

gonna get this. And he like picks up a stick and he like goes like assault this poor copperhead that's sitting on the trail. And so like at like 16 years old, I had to go and like shoulder this guy out of the way.

Speaker 1

46:46

And I like got the thing by the tail and used a stick to very gently just put it off the trail. Copperhead was not gonna do anything to him, but he wanted to beat his chest and show his wife that he was tough. But then in India, I've lived in India for 5 years at this point in and out, periodically. And snakes are always getting into people's kitchens.

Speaker 1

47:08

1 time we had a king cobra get into someone's kitchen, an 11-foot snake, like a monster, like a god of a snake. This thing stood up, you know, would stand up, he'd be able to look at you over the table. And this terrifying monster thing, this giant gorilla dog thing, like we caught it with 1 of the local snake catchers and we brought it out and he goes, you know, I wonder why I was in the kitchen. Yeah, looking for food, and they go, no, they eat snakes.

Speaker 1

47:36

King Cobra, Ophiophagus hannah, they eat snakes. And he goes, she's thirsty. And so we got a bottle of water, and we got footage of this, and she's standing up. She's going, don't make me kill you, don't make me kill you, you're scaring me right now, I don't wanna kill you.

Speaker 2

47:50

We

Speaker 1

47:51

took the bottle of water and we poured it on her nose and she started drinking. You could see her just drinking and the snake just took this long drink, she drank a whole water bottle

Speaker 2

48:01

and

Speaker 1

48:01

then said, thank you so much

Speaker 2

48:03

and

Speaker 1

48:03

crawled off. And it's like, to me, the fact that people are scared of snakes, they have symbolic hatred of snakes, you know, if someone's evil and sneaky, we call them a snake. And like, to me, it's like, when I take volunteers or researchers or students out into the jungle and we find an emerald tree boa or an Amazon tree boa or a vine snake and it's like, it's 1 of the few animals that you can't really catch a bird and show it to people.

Speaker 1

48:29

You're gonna scare the bird, its feathers are gonna come out, you might give it a heart attack. Snakes, you can lift up a snake. You know, if there's a snake in the room right now, I could lift it up and say, Lex, here, this is how you hold it. And we could interact calmly with this thing and then put it back on its branch and then it'll go.

Speaker 1

48:43

And I've seen what that does to people. I've seen how, the wonder in their eyes. And so to me, snakes have always been this incredible link to teach people about wildlife, about nature.

Speaker 2

48:53

Because they have naturally a lot of fear towards this creature and to realize that the fear is not justified, is not grounded, or is not as deeply grounded in reality. Of course, there's always New Yorker snakes, right? There's always gonna be an asshole snake here and there.

Speaker 1

49:09

Coming for me, man.

Speaker 2

49:13

Well, okay, so back to the anaconda. How do you catch an anaconda? Because it's such a 25 foot or even 12 foot, these giant snakes.

Speaker 2

49:23

How do you deal with this creature? How do you interact with it?

Speaker 1

49:27

We had to learn how to do that. Because 1 of the first ones we caught that I would say, maybe like a 16 footer, which is no joke of a snake, girth of a basketball, let's say. We're on the canoe and this is the early days.

Speaker 1

49:41

Now we're at a whole different level, but this is back when we were barefoot and shirtless and just guys in the Amazon. And JJ's like, get out, you know, I just listened to him. He'd be like, get off the boat. You come from the top.

Speaker 1

49:53

We're gonna come from the bottom. I was like, okay. I just did as I was told. I came in, the snake is all curled up, dead asleep.

Speaker 1

50:00

She's got some butterflies on her eyes, trying to get salt and stuff. And all of a sudden I see the tongue, zoom, zoom. I'm like, she's awake. And I'm like, guys, guys, guys, she's, and they're paying attention to not crashing the boat, to getting over there.

Speaker 1

50:12

We're all trying to run. Snake starts going into the water. So I run ahead, grab this snake, get her by the head. So you got her by the head, you think, okay, she can't get me.

Speaker 1

50:22

I got her right behind the head and it's about this thick, the neck.

Speaker 2

50:25

What's that feel like, sorry to interrupt, like grabbing this thing with this giant head?

Speaker 1

50:30

It's exciting, it's amazing, it's scary.

Speaker 2

50:33

How hard is it to hold?

Speaker 1

50:34

It's not that hard to hold. The scary part is the moment of, it's like if you've ever done a cliff dive or something, it's that moment where you go, do it, do it, the time, like do it, and your body's going, do not do that. And then you're like, I gotta just

Speaker 2

50:47

do it.

Speaker 1

50:47

And you do it.

Speaker 2

50:48

Because you can't just gently like flirt with it. You have to grab the thing.

Speaker 1

50:51

No, and it's like crossing the street when there's a bus coming. It's like if you hesitate, it's more dangerous. So like you just, you go for it and I got her.

Speaker 1

50:58

And I was like, I got her. And then a coil goes over my wrists. And all of a sudden my wrists slap together and you feel this squeeze that can crush the bones out of an animal bigger than me. And the next coil comes very quickly over my neck.

Speaker 1

51:12

And now I'm on my knees with my arms tied. If I wanted to let go of the snake, I couldn't, and my shoulders are coming together and my collarbone is about to break. And I tried to yell for JJ and all that came out was, there was nothing. And so that's what they do to their prey, you know?

Speaker 1

51:25

So I attacked, as far as the snake knows, I attacked. She doesn't

Speaker 2

51:28

know that, I just wanna measure her. You started off as the big spoon, but then the snake became the big spoon.

Speaker 1

51:34

The snake very much became the big spoon. And I would say I was 15 seconds away from having my entire rib cage collapsed, and then JJ showed up and grabbed the tail and just started unwrapping this thing. And then we got, but now we have a system.

Speaker 1

51:47

Now we know like, you know, I'm always, I've gotten more head catches than anybody, so I'm usually point guy and you know. You're the first,

Speaker 2

51:57

the point guy. Okay, taking the big risky first step.

Speaker 1

52:02

Yes, although it could be argued that there's a similarly large risk for the tail guy because Anaconda's defense is to take a giant projectile shit. And so the person that gets the tail is gonna smell like Anaconda for at least a week.

Speaker 2

52:15

Yes, it's the least pleasant. You're taking the most dangerous 1 there.

Speaker 1

52:20

They have the least pleasant job. This is fascinating. But what's really fascinating though is that because they're the apex predator, they're eating the fish, they're eating the birds, they're eating everything, and everything in this riparian ecosystem is absorbing the mercury that's coming off the gold mining in the region.

Speaker 1

52:35

And so anacondas can be indicative for us of how is mercury moving through this ecosystem. And this is a region where we've lost hundreds of thousands of acres to artisanal gold mining where they use mercury to bind the gold. They cut the forest, burn the forest, and then they run water through the sand and the sand particles have bits of gold in it, not chunks, but just little, almost microscopic flecks of gold. And then they use the mercury to bind that, and then they burn off the mercury, and that vapor goes up into the clouds, just like everything else, it's all connected down there, and then rains down into the rivers, and so the people in the region are having birth defects from the amount of mercury that's in the water.

Speaker 1

53:16

And so we were starting at 1 point when we were doing most of our anaconda research, we were learning things like these animals actually aren't just ambush predators, which is what most of the literature would tell you is that anacondas are ambush predators. No, they actually go hunting. They'll go find clay licks and salt deposits and they'll wait there. They'll actually pursue animals.

Speaker 1

53:35

And we were trying to take tissue samples to find out if anacondas could be used to study how Mercury's moving through the ecosystem. And so that was really, it became, Can we use these animals not only as ambassadors for wildlife because everybody wants to see the anacondas, but also what can we learn from studying this very, very little understood apex predator? And 1

Speaker 2

53:56

of the things you can learn is how mercury moves through the ecosystem, which can damage the ecosystem in all kinds of different ways.

Speaker 1

54:03

Yeah, it's brutal, man. The gold mining that's happening down there is, it's funny because we've been hearing a lot recently about like the cobalt mines in Africa. And it's like where we are in the Amazon, We were down there with ABC News, I wanna say like a year and a half ago, with my friend Matt Gutman, who's the chief correspondent for ABC.

Speaker 1

54:24

And he wanted to see the Amazon fires, he wanted to see some wildlife, he wanted to see the areas that were protecting, and then he goes, I wanna see the gold mining areas. And I'd never gotten in so deep, but we met these Russian guys, you can't go with the Peruvian, they will kill you. Like our lawyer's father was assassinated for standing up to the gold miners. There was 2 Russian guys though who had a legal mining concession somehow, way out past the machine gun guarded limit of the Pompas, which is where they do all this gold mining.

Speaker 1

54:53

And we got in there and took footage of the desert that is forming in what used to be the headwaters of the Amazon rainforest. And it's like, there is a massive global scale ecological crime happening down there that you can see from space from this unregulated gold mining. And the cops can't go there because they will be murdered. It's completely lawless.

Speaker 2

55:16

What's the machine gun limit exactly?

Speaker 1

55:18

It's the border of this area that they call the Pompous, which is where the rainforest has been cut and completely destroyed, and it looks like Mars. It's just sand. And inside of this area are gold miners, and we tried to get in there to film years ago and there's just a lot of guys with machine guns who don't let that happen.

Speaker 2

55:38

And what the Russian guys have access to?

Speaker 1

55:39

The Russian guys had access somehow. They'd come down with a bit of money and they had a new system, yeah. And actually what was interesting is while I was in there, they're very friendly and really, really 2 friendly gold miners.

Speaker 1

55:52

And 1 of them while I was there, he kind of tapped me on the shoulder. He was like, you know, look at those guys. He was like, those guys over there? He goes, I just heard them say your name.

Speaker 1

56:02

And he goes, that's not a good thing. He goes, they know exactly who you are. He goes, I wouldn't keep posting to Instagram about gold mining in the Amazon. And I was like, thanks for the warning.

Speaker 1

56:13

And then, you know, In June, somebody pulled up beside me on a motorcycle and I got a more stern warning, but.

Speaker 2

56:19

They pay attention to the flow of information because they don't want the world

Speaker 1

56:23

to find out. Oh, the last thing they want is to be shut down, but the gold miners are notorious for, you know, just whacking people and throwing them in a pile of gold mining leftovers. It's really like the Peruvian government has to get the military to go after them.

Speaker 1

56:41

Like the work we've done with gold miners, converting them into conservationists has all been like, I mean, I've seen the Peruvian Navy come down and literally blow up gold mining barges, and it's a war. It's a war being fought in the Amazon.

Speaker 2

56:55

So it's possible to convert them into conservationists? What's that process like? Or is that like, you say that in jest?

Speaker 1

57:03

No, I say that in absolute sincerity. We went up river, up the Malinowski River several years ago, and I think it was 2018, and everyone was like, you are going to die. Like, you will be shot and killed.

Speaker 1

57:16

And the reason we were able to do it with relative safety was that the gold miner that we were going with was the brother-in-law of 1 of my closest friends down there, our expedition chef and 1 of the directors of Jungle Keepers. And they said, look, you can go, just keep a low profile. And so I went up with a photographer and we spent a week there and dead animals everywhere, deforestation everywhere. I mean, the things that we saw were so horrible.

Speaker 1

57:43

And we're living with these gold miners that are, you know, they're getting their gold, they're burning off the mercury. I watched a guy smoking a cigarette, burning the mercury off of his gold with the vapor going straight into his face with his child right there. I mean, unbelievable negligence of just sanity. And then towards the end of the week, the Peruvian Navy comes down the river and everyone starts scrambling.

Speaker 1

58:09

And I was like, I'm just going to sit here with my hands up because, you know, and they didn't even stop. They found the gold mining barge, you know, they have a floating thing in the river that just plumbs the bottom of the river, just sucks all the sediment up, and they stopped and they strapped a bunch of explosives to this motor, and good Lord, the sound of this explosion, and there was just hot metal raining down all over the place and then they just went, a bunch of guys in fatigues and they just kind of like looked at us like, peace. And I sat there with this gold miner and I went, now what? And he went, well, now I gotta go get a new motor.

Speaker 1

58:41

And I went, why don't you just do something else? And he goes, what else is there? And I went, look what we do. And I sat there with my phone and I was like, see this, these are pretty tourists.

Speaker 1

58:52

And we feed them food and we show them tarantulas and macaws and he looked at this and he went, wow. He goes, that looks like so much fun. And I went, it is so much fun. I said, we bring students to the jungle.

Speaker 1

59:05

He goes, so you're saying if I build you a lodge, you'll bring people? I said, yeah. And I came back a year later and he sat there with a chainsaw, a handsaw, and some nails, and he cut down like 17 palm trees and he built an ecotourism lodge.

Speaker 2

59:20

So you give him another channel of survival of making money.

Speaker 1

59:24

And that's what we've been doing through Jungle Keepers for loggers and for all kinds of extractors is just saying, look, what do you make? You make $15 a day destroying the ancient trees of the jungle. What if we paid you $35 a day to have a uniform and a job and health insurance and security and you just protect it and use all of the jungle knowledge you've gained as a logger to protect this place.

Speaker 2

59:49

Who are the loggers trying to destroy the Amazon? Can you say a little bit more about it? Is that as a threat to the Amazon rainforest?

Omnivision Solutions Ltd

- Getting Started

- Create Transcript

- Pricing

- FAQs

- Recent Transcriptions

- Roadmap